Systems Stress Test

I swear this won’t be another blog about a virus. OK, maybe a little bit.

A few years back I wrote about learning to see systems – food systems, transportation systems, financial systems, governance systems, etc. In order to build our social resilience, we’ve got to know what systems we rely on, and what they are vulnerable to. It’s not that hard to do, but until you’ve seen them in action, they can be hard to pick out in the everyday noise of the world.

Well we’ve got a natural experiment going on right now with the COVID-19 crisis, which is actually highlighting systems for us. What is this experiment showing us?

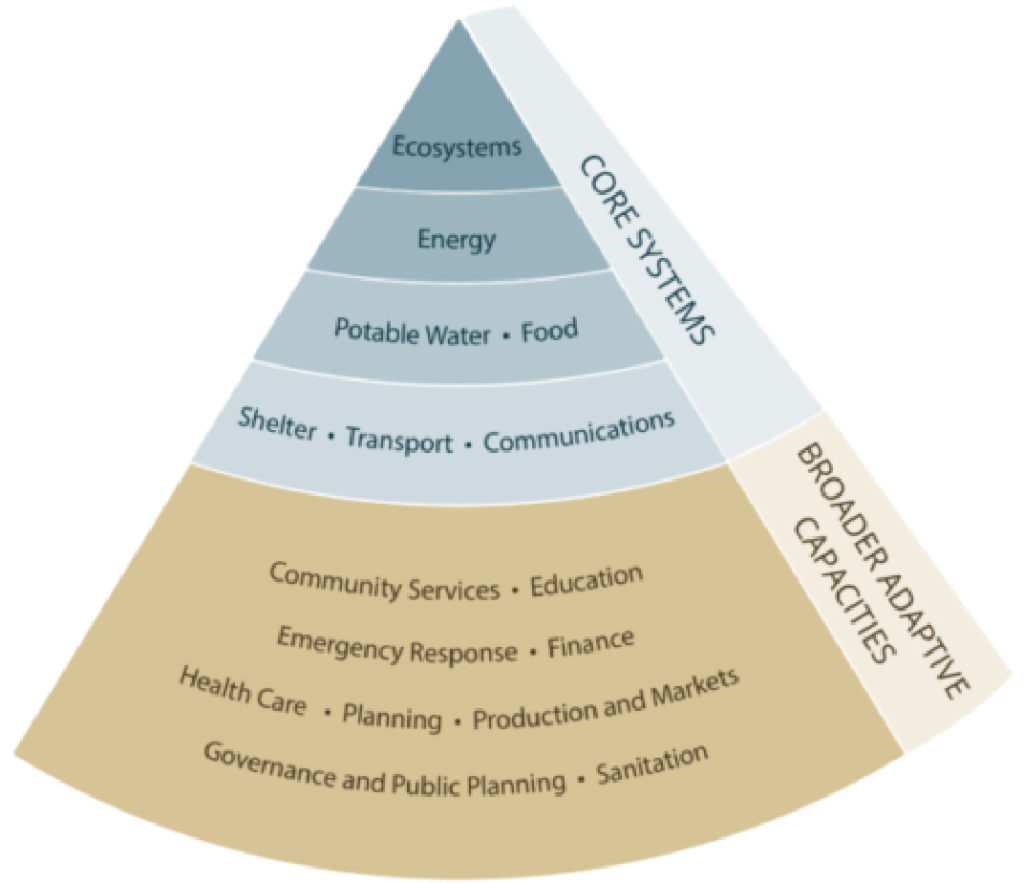

To sort out the welter of data, I like the framework developed by ISET-International, which puts these systems in a hierarchy.[1] The graphic here illustrates the systems we depend on, showing which are more fundamental, and which we can work around. That is, all of our systems are based on the ecosystem: if it stops raining (or doesn’t stop), if temperatures go haywire, if we can’t breathe the air, then all other systems are affected. (Good thing we know that would never happen….)

After that comes energy: if the power goes out, or gas supplies are disrupted, or in some countries if firewood becomes scarce, then food systems, manufacturing, transport, education, and a heap of other things grind to a halt. These are called “cascading failures,” where the failure of one system causes failures of others downstream.

So what are we seeing now? You could say the COVID-19 situation is an ecosystem failure. That is, a pathogen in our system is ravaging human health. So in response, we institute physical distancing measures, and curtail economic activity. In the graphic, you can follow these knock-on effects down the line. Not all systems are affected, so let’s look at the highlights of ones that have been. I’ll use what I’m seeing happen in my area to try to make it concrete – a trip to my local supermarket.

Core Systems

First, in heading out the door I put on my face mask and latex gloves, to insulate me and others from the virus – a disrupted ecosystem. In my situation, my shelter has not been affected, but for many others, losing their income has made it hard to pay their rent or mortgage. I get in my car and pull out into the street. For me the energy and transportation infrastructure still work, though in the energy industry the reduction in demand is contributing to a collapse of oil prices. This collapse is in turn creating a difficult set of problems for industry and super low prices for consumers.

I get to the supermarket, which for all appearances is working as normal – an “essential service.” But going inside, I see the empty shelves show that the food system has been disrupted. But the shortages of the first few weeks have now faded, showing the problems in the food system have been due more to distribution than production – shelter in place means stock up now, so demand spiked for quarantine food like rice and canned food. As I overheard in line one day, “if I can still get avocados then we’re doing OK.” In fact, over production may be a problem: plunging demand from restaurants, company cafeterias, and school districts are leading some farmers to plow under their crops.

Broader Adaptive Capacities

Paying for my groceries goes smoothly – the financial system is largely intact. It reminds me of the last time we had a major disruption here, huge floods in 2013. Credit cards and cash machines still worked, so people were able to buy supplies and dig themselves out – had those gone out, the disaster would have been much worse. There will no doubt be big disruptions later on – rent and mortgage payments not made and business loans in arrears will put a huge strain on the financial system, especially since the protections put in place in 2008-9 have been largely dismantled. (Those who don’t study history….)

And while the supermarket is fully staffed, many have called in sick, or feel it’s just not worth the risk of going to work. In contrast, the strain on the health system is huge: a large increase in patients coupled with the need for isolation wards and shortages of supplies has increased costs to hospitals, while the elimination of elective surgery and visits have gutted revenue. And even more disturbing, these strains have endangered staff. The system is still working here in Colorado, but in areas with higher numbers of patients, the bodies are, literally, piling up. If you were unlucky enough to not have health insurance, good luck. And, unlike countries with better health system coverage, the US system with its high deductibles discourages you from getting checked out if you have the sniffles or a bit of a fever, thus increasing the risk.

When I finally get home, I see my family members who have been laid off or their businesses gutted, figuring out how to get by. Markets and production have been profoundly disrupted, more by the public health measures put in place than the virus itself. Unlike the 2008 economic collapse, though, most economic fundamentals are sound. People have lost jobs, and businesses revenue, some permanently. And debt and bankruptcy should skyrocket even after we’re back at work. But for the most part there’s every reason to believe many businesses and jobs will spring back as soon as people can leave their houses again. Governments are pumping trillions into their economies, much of it to support payroll for regular employees, which should ease the damage somewhat. And there have been some winners – mail order services and supermarkets have been hiring as fast as they can to meet demand.

So how are we doing on the resilience stress test? We have seen some serious knock-on effects from an ecosystem disruption, but not a total cascading failure, as we saw in Superstorm Sandy in the US or floods and hurricanes in South Asia in recent years. Hardest hit are the market and health systems. The resilience of the energy and communications sectors have made managing the whole thing far easier. And let’s not forget social networks – they have been disrupted profoundly, especially for families with elderly or immune compromised members. As in all crises, many have actually strengthened their social networks as people connect with each other in solidarity, or just because they have more time.

[1] Full disclosure: I worked at ISET for a few years, and consult with the organization from time to time. Great people. This graphic is adapted from Moench, M., S. Tyler, et al. (2011), Catalyzing Urban Climate Resilience: Applying Resilience Concepts to Planning Practice in the ACCCRN Program (2009–2011), 306 pp, ISET- Boulder: Bangkok, p. 44.